Ed. Note: This post is a bit of a doozy, hence my delay in getting it up. I recommend getting a cup of (equitably sourced) coffee and sitting down with this for a few minutes.

I’ve alluded a couple of times to Raw Material, which is the organization behind El Fénix. Now that I’ve visited their office here in Colombia, I can expand a bit on their mission and how they work, and how they’re working to address some of the biggest problems in the coffee industry.

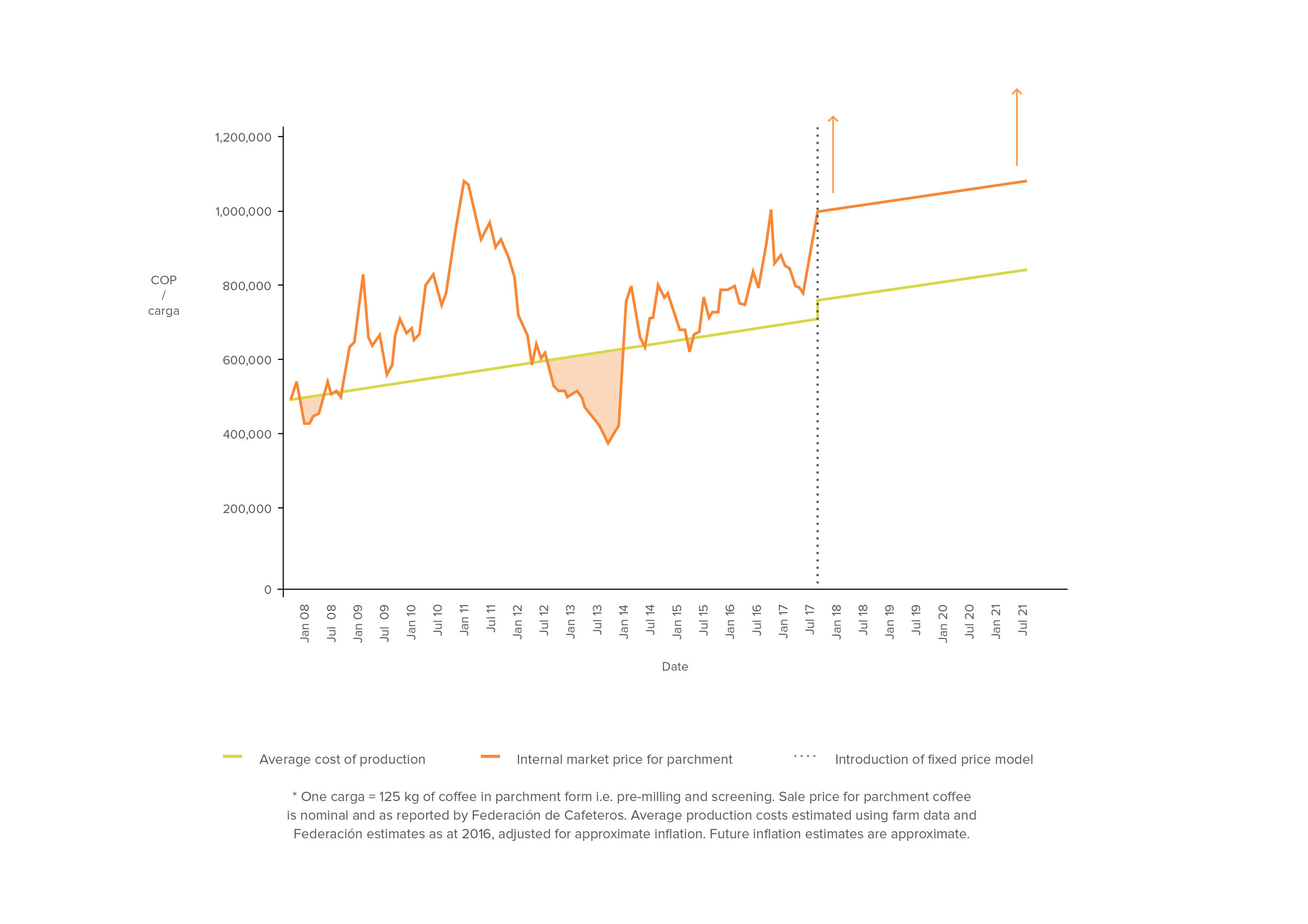

Raw Material is a boutique specialty coffee exporter with with projects in Colombia, Timor Leste, and Rwanda (and a future one in Burundi). Their primary mission is improve price stability at the farm level and “distribute income more equitably along the supply chain.” (From their website) The way they do this is by guaranteeing an income to producers in the form of a fixed price purchasing model. This is the core part, and something that’s quite unique: they are not something like fair trade, with a minimum price. Raw Material pays the exact same (inflation-adjusted) amount to producers, year after year. By reducing uncertainty, Raw Material can provide an economically sustainable opportunity for coffee producers.

In order to guarantee this fixed price, Raw Material sells directly to the specialty market, which is generally willing to pay a premium for better coffee and/or socially responsible coffee. However, this premium isn’t the kind of thing that customers will have to fork over boatloads of money for: Miguel has calculated that the trickle-down markup of the fixed price model for customers works out to about five cents per cup. Of course, this isn’t nothing (especially in the low margin coffee shop space which I am getting to know pretty well!) but it is an eminently reasonable price to pay.

How it Works

Coffee is purchased from producers in Colombia in parchment, the protective shell of the bean that encases it during processing, so prices for producers are listed for parchment coffee. The parchment is typically bought at Associations, which are run in partnership with the Federacion Nacional de Cafeteros de Colombia (FNC). The FNC posts a list of the daily price of parchment, which is related to the New York “C” price – the commodity exchange that coffee is traded on – and the USD/COP conversion rate.

One Carga of coffee is 125 kilos – about as much as a donkey can carry! An Arroba is 1/10 of a Carga, so there are 12.5 kilos per Arroba. Raw Materials sets a fixed price of 100,000 pesos per Arroba for parchment coffee. This is about a 25% premium over current market prices. But let’s back up a second – Raw Material’s model is a direct response to a fundamental difficulty with the coffee market, which is the volatility of the New York C Price:

While the C price does not directly translate to the FNC’s daily price, they are closely correlated. As you can see, the C price has had some enormous spikes and dips and has generally not risen over the last 30 years. What’s most troubling about the C price is that it has very little correlation with the cost of production for the majority of coffee producers. The C price is almost entirely dependent on forecasted production of coffee in one country: Brazil. Brazil produces about 50% of the world’s arabica coffee in large commercial and mechanized farms, so any changes in Brazilian production has a huge impact on the global C price. Funnily enough, the C price is probably a much better proxy for the weather in Brazil than it is the average cost of coffee production. (Indeed, many coffee futures traders get reports every morning about weather forecasts in southern Brazil.)

Estimating the cost of production for coffee is another one of the core difficulties in creating a sustainable coffee supply chain. The SCA’s recent literature review concluded that “more research is needed” to verify claims of profitability. Roast Magazine had a good article in the last issue about cost of production broken down in a few cooperatives, which I wrote about from Bogotá. In general, though, Miguel told me that the cost of production for producers in Colombia right is roughly $76,000 COP per arroba, while the FNC’s price is about $79,000. Fortunately, the price at the moment can at least cover basic costs of production at the moment, but coffee is clearly not a hugely profitable enterprise.

One last thing to keep in mind is the conversion from parchment prices to “Free On Board” (FOB) prices for green coffee. The first thing to consider is called the “Factor de rendimiento,” which we can simply call the yield. The yield tells you how many kg of parchment coffee will yield 70kg of Excelso grade export coffee. Uniform Good Quality (UGQ) excelso is at least screen size 14 (the beans are at least 14/64″ in size) and has a maximum of 12 primary defects and 60 secondary defects per 500 gram green sample. This is abbreviated UGQ 12,60. If your coffee has a lot of defects, you will need more kg of parchment coffee to yield 70kg of UGQ green. In general, 17% of the coffee’s weight is lost in the dry milling process, so you’d need about 82kg of perfect parchment to yield 70kg of excelso green. The standard yield is 92.8kg of parchment for 70kg of UGQ 12,60. As you can see on the FNC’s price chart, prices of the day are posted for this standard yield.

Figuring it Out

If the FNC is paying $79,000COP per arroba with a standard yield of 92.8, we can do some quick maths:

$79,000COP/arroba parchment * 1 arroba/12.5kg * 92.8kg parchment/70kg green = $8,378 COP/kg green. This is $2.62 per kg, or $1.18 per lb paid directly to the producer. (Next time you buy a pound of coffee at the supermarket, realize that about a dollar of that is going to the producer.)

To get to Raw Material’s FOB price, you tack on a $.30/lb export cost, which includes a 6 cent tax paid to the FNC, transportation to port, and more. Finally, Raw Material takes a 15% margin to cover operating costs, so if Raw Material was paying 79,000 COP/arroba, they would charge $1.70/lb FOB. However, Raw Material actually pays 100,000COP/arroba, so:

100,000COP/arroba * 1/12.5 * 92.8/70 = 10,605COP/kg green = $1.51USD/lb to the producer. Remember that cost of production is currently around 76,000COP/arroba, or about $1.15USD/lb green. Adding on import and overhead yields $2.08USD/lb FOB, which isn’t far off from their actual FOB price of $2.36USD/lb.

So that’s how the economics of it works! You’ll notice that $1.70 FOB is not the $1.05 FOB listed on the C market. This is because the FNC sells coffee futures contracts, usually for a better price than for shorter-term contracts. For example, it may sell contracts for this December at $1.50, even though the C price for buying coffee right now is only at about $1.05. In this way, the FNC’s daily prices are not directly linked to the C’s price of the day, but instead can somewhat insulate itself against volatility.

How’s it Going, Though?

For any social business the real question is scale. The more people you help, the better you’re doing, and scaling isn’t as easy with a double- or triple bottom-line approach. This is especially true for Raw Material, because their business model is dependent on direct connections to specialty market. Specialty roasters are willing to pay premiums for quality and for socially conscious purchasing, and Raw Material can offer both of these important traits. The offside investment, though, is in the time it takes to cultivate and maintain this personal relationship.

Last year, Raw Material exported 17 containers from Colombia. Each container can hold 275 bags of green coffee, so RM purchased and sold about 430,000lbs of parchment coffee from producers last year. This year, they’re on track to send somewhere in the mid-20s, which is a significant increase. They’ve worked with 400 total coffee farmers so far, which translates to about a 1500 person impact, including the farmers’ families. Luckily, purchasing can scale somewhat linearly, while selling might scale logarithmically for a while. The main bottleneck at the moment is almost entirely logistics: accounting for, cupping, grading, selling, and shipping coffee is a lot of work, and it requires a lot of people to work on it. At the moment it’s just Miguel and Caterina, who works with him in Armenia, in Colombia.

Cool Beans

Raw Material is a very impressive company that directly addresses some of the core deficiencies and social inequities of the coffee market. They’ve taken a novel approach that not only primarily provides economic sustainability to struggling producers but also can help roasters and purchasers better predict their future expenditures, as FOB prices are also fixed.

El Fenix has mostly grown as a side project of Miguel’s and Raw Material’s to experiment with coffee production techniques and varietals in Colombia. El Fenix can probably produce about 40 bags at the moment, which certainly isn’t very much in the scheme of things. The idea is eventually to have El Fenix producing some of the top microlots that Raw Materials sells, including esteemed Geshas, Mokas, and Wush Wush coffees that could be sold for significant premiums. At this point, though, El Fenix is still in the pretty early stages of its development and will continue to grow with investment from RM and as the trees on the farm mature.

So that’s what I’ve got for you today! I have some other very exciting news, which is that many of my samples finished drying, so I milled, roasted, and cupped them this weekend! I’ll share my preliminary findings in a post today or tomorrow.

Have a great one, and I hope you learned something!

Alex

One thought on “Raw Material and the Business of Coffee”