I spent the last weekend at La Palma y El Tucán. To call La Palma a farm is quite the understatement; as best I can figure, it’s the future of coffee. Although it was my first time really interacting at origin with producers, even I could tell that La Palma is something special.

La Palma y El Tucán began as a project by Felipe Sardi and Elisa María Madriñan to “shatter the status-quo by implementing groundbreaking social, environmental and technological innovations.” They purchased a 18 hectare lot about 1.5 hours southwest of Bogota whose unique geography affords it almost 10 different micro-climate regions for growing coffee. Soon, they built a state of the art wet mill station and a number of drying beds to process coffee with. Finally, they added a boutique hotel on the farm that includes 9 beautiful cabins situated amongst the coffee trees overlooking their view of the valley ahead.

Then, they started producing coffee. La Palma’s 18 hectares is host to a number of different rare coffee varietals, including SL-28, Moka, Gesha, Sidra, and more. Each of these require different growing conditions, which they are able to achieve through their several microclimates and agriculture practices, like planting more or fewer shade trees. The SL-28’s that were near my cabin, for instance, got a significant amount of direct sunlight, and the air around them was much less foggy than it was down the farm. The Geshas near the cupping lab, though, were heavily shaded, and are basically inside of a cloud most of the time.

Right off the bat, it’s clear La Palma takes immense care in their agricultural practices. Successfully producing so many immensely finicky varietals is a sign of exquisite coffee farming and attention to detail, so it’s no surprise that their coffee is delicious. But the trees they care for are just the start of La Palma’s grand project of “shattering the status quo.”

“Traditional” Coffee Farming in a New Light

A core part of La Palma’s mission is to “revitalize the coffee-growing culture in our region” through partnering with local coffee growers. The status quo holds that traditional coffee farmers are largely incapable of producing specialty coffee for a number of reasons, chief among them their lack of access to exotic varietals. Most coffee producers in Colombia grow Castillo or Colombia, two genetic hybrid varietals that were bred for pest and disease resistance. (Colombia is the name of a coffee varietal, in addition to my current whereabouts; it was created by the Colombian coffee research authority.) The vast majority of coffee buyers will tell you that Colombia and Castillo are known for having poorer flavor profiles in the cup.

Tree type is only one of a number of hurdles that face traditional coffee farmers. Traditional Colombian farmers also typically mill, process, and dry their own coffee. This constitutes an enormous investment of time, space, resources, and equipment for farmers: in addition to tending to their crops, they must operate a small-scale mill, wash and ferment their own coffee, dry it, and transport it in parchment to sell.

So far, this seems to me a the core problem of current coffee production: “farmers” and “producers” are interchangeable words, yet they refer to wildly different activities and skill sets. Coffee farmers are excellent at farming coffee. Milling, fermenting, and drying coffee, on the other hand, are a whole different ball game.

Here’s where La Palma (and El Fénix, where I’m going next week!) comes in. La Palma has constructed a large enough milling station that they can buy coffee still in the cherry from local farmers and process it themselves. In doing so, they cut out an enormous chunk of costs for coffee producers, and allow them to focus on what they do best: farming coffee.

Furthermore, by centralizing milling, fermentation, washing, and drying, La Palma can train and employ specialists whose only job is to conduct one part of the coffee production process. For example, La Palma’s “about us” webpage lists all the following roles as members of its team:

- “The Dedicated Grower”

- “The Obsessed Alchemist”

- “The Talented Artist”

- “The Experienced Technician”

- “The Crazy Scientist”

- “The Passionate Founders”

Such a clear delineation of roles not only cuts down costs in production by increasing efficiency; it allows each actor to become a craftsperson in their trade. This is almost certainly why La Palma is able to capitalize on something it is world renowned for: its fermentation.

Fermentation at La Palma

Yesterday, I told you that after milling, you ferment coffee for 12-36 hours. I’m not wrong: many people will tell you the same thing. La Palma will not.

I was walking around La Palma today talking to Felipe Pinzon, the outgoing “director of experience,” or client-facing coffee guy. We had just finished a cupping and I was really impressed by the fruitiness of so many of the coffees on the table. I asked how long their fermentation usually lasts, and if it’s more towards the upper end of the 36-hour limit.

“No, closer to 100 hours for that one.”

WHAT!!!

I was absolutely dumbfounded. I had never heard of anything close to this before. This would be like if I asked you how long you baked those cookies for and you said 12 hours. It’d be like if you asked how long you caramelized those onions for and someone said 3 days. It is absolutely crazy.

Fermentation is a very complicated process that at its core involves a breakdown of sugars in the coffee cherry. To be honest, I don’t really know much about the chemistry of fermentation, but I do know this: you definitely don’t want to over-ferment them coffee! One of the defects we trained on in the Q was a ferment defect, which is when a cherry has been over-ripened or left in a fermentation tank for too long. Its tell-tale sign is an alcoholic note, like red wine or rum.

Being able to expertly control fermentation is La Palma’s secret sauce. Felipe told me that being able to stretch the fermentation times of coffee so long is one of the most important ways that La Palma is able to bring out the flavors of the coffee. It’s also one of the most difficult things for smallholder farmers to control, as they lack access to advanced instrumentation like Brix meters for sugar content or acid content measurement devices. Even if they did have such instruments, it’s incredibly difficult to control the mix of microorganisms, yeasts, and bacteria that fester in a fermentation tank.

Lessons Learned

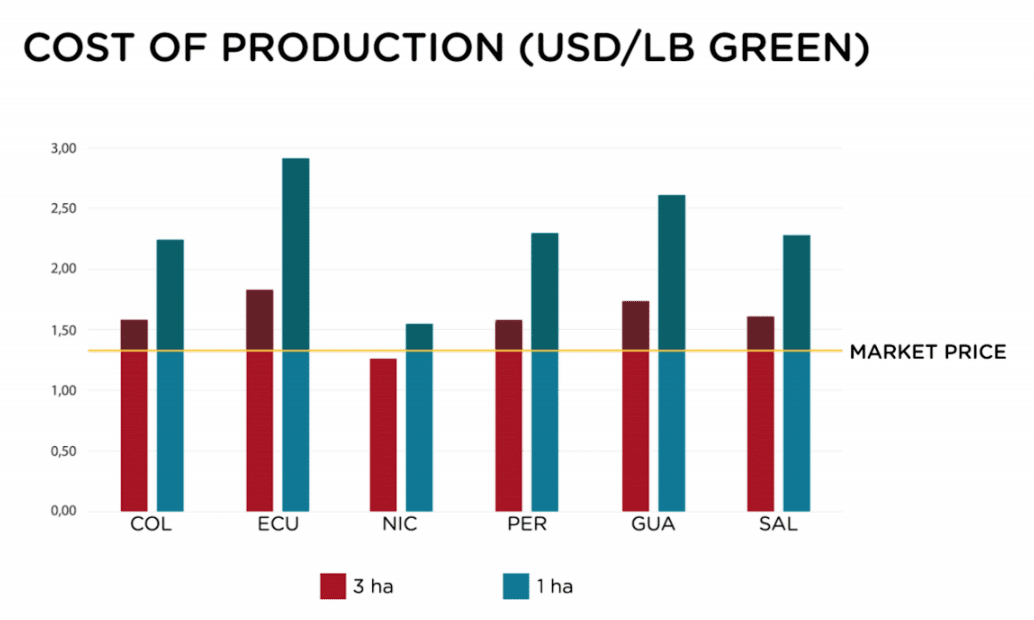

The name “La Palma y El Tucán” comes from two endangered species that are present at La Palma: the Wax Palm and the Emerald Toucan. Ignacio, who showed me around the farm and explained much of their processing to me, told me that the name carries multiple symbolisms. First and foremost, coffee production in Colombia is slowly becoming endangered due to a number of reasons. Increasing costs of production due to unpredictable weather patterns, more susceptibility to la Broca and la Roya, and worsening soil content makes it more expensive to grow coffee. Simultaneously, increasing variability (and plummeting) in the C-Price and local buyers’ prices means farmers are earning less for their coffee. All this points to less and less motivation to maintain familial coffee farms – La Palma states that the average age of a coffee farmer in Colombia is now over 60.

But the Wax Palm and the Emerald Toucan are important for another reason. They are symbols of Colombia’s beautiful biodiversity and agricultural potential. And crucially, they function together in a symbiotic relationship. When allowed to thrive, the Emerald Toucan spreads the seeds of the Wax Palm and helps it grow and blossom. As I saw firsthand, La Palma can help reinvigorate the historic symbolism of Colombian coffee farming through better production practices, cooperative partnerships, and specialty market access.

Today, I got to cup coffees from the neighbors of La Palma who are featured in their Neighbors & Crops program.

We went through the first table, which featured 13 wildly different coffees. Flavor notes spanned from peach yogurt to hazelnuts to milk chocolate to kiwi fruit. As Felipe said, we got to “taste the whole rainbow” on that table. I was super impressed by the consistent quality on the table, and how many different coffees La Palma was able to produce.

And then, Felipe dropped the hammer: every single one of those 13 coffees was a Castillo grown by a traditional Colombian coffee farmer. Not a single one of those farmers owned a Brix meter or had read the SCA’s Coffee Agriculture guide, yet they all were able to produce incredible coffees. Even that peach yogurt coffee, which I scored at an 87.5 (stunningly good!), was grown in a very traditional manner by a 3rd-generation farmer.

Here is the lesson that I have learned from La Palma: specialty coffee is accessible. There are certainly hurdles to achieving it, some of which I’ve outlined here and some of which I’ll continue to write about on the blog, but no farmer is incapable of producing specialty coffee. The specialty industry hypes up the latest fad variety and processing techniques so much that anything not new must be old and lame. In doing so, we not only do a disservice to ourselves as coffee buyers, but more crucially to the hundreds of thousands of traditional farmers who deserve so much more credit than we give them.

Bits and Pieces

There was a lot more about La Palma that I wanted to say and a lot more pictures I wanted to upload that didn’t fit in the story I wanted to to write. So here they are!

First of all, the food at La Palma is insane. Many of their ingredients are grown on their organic vegetable farm, and the chef whips up incredible vegetarian dishes from them.

Breakfast bar

Cabbage stir-fry with veggies

Lentil salad with Mango Juice

Cauliflower risotto

Fresh veggie spring rolls

Pasta with veggies

Second, the cabins are absolutely gorgeous. Not only do they have a beautiful view, but the insides are stunning and generously accommodating.

Outdoor shower and all!

Replete with hammock, of course

The view from bed

Third, the main terrace of the hotel is stunning. It has a coffee bar, a regular bar, a bunch of tables to eat or lounge at, and the kitchen. It also looks out on one of the best views I’ve ever seen.

Lastly, I had an awesome time learning about wet milling and processing from the people who do it!

I had an amazing weekend, and I have a lot of thoughts floating around in my head still. They’ll keep creeping out over the next few days, but in the meantime I hope you enjoyed this first look at coffee production.

Alex

One thought on “The Palm, the Tucan, and the Future of Coffee”